Vol. 10. N° 2

Julio - Diciembre del 2021

ISSN Edición Online: 2617-0639

https://doi.org/10.47796/ves.v10i2.566

ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL

Underground innovation in mexican sme

Innovación

clandestina en pymes mexicanas

Saúl Alfonso Esparza

Rodríguez

[1]

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9900-6159

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9900-6159

Jaime Apolinar Martínez

Arroyo [2]

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9926-4801

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9926-4801

Enrique Esquivel

Fernández

[3]

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9005-7227

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9005-7227

enrique.esquivel10@yahoo.com.mx

Aceptado: 20/10/2021

Publicado

online:30/11/2021

![]()

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Small and Medium

Enterprises (SMEs) are significantly relevant in the Mexican economy,

employability, and innovation. In terms of understanding innovation on those

companies that goes beyond formal innovation, the present work proposes to

analyze “underground innovation”.

Methodological design:

Using the data available in the National Productivity and Entrepreneurial

Competitive Survey for Mexican SME´s (ENAPROCE), we made a correlation analysis

among organizational innovation, marketing innovation, process innovation, and

product innovation to understand the relationship among different types of

innovations which are usually related; then, a partial correlation test having

the number of registered industrial

property (Brands, Patents, Utility Models, and Industrial designs) as a

variable control to obtain the partial relation coefficient among variables

related to informal non-registered innovation. The partial relationships among

interactions related to stakeholders and underground innovation in Mexican SMEs

are classified in three categories: positive (the person taking decisions;

directive and supervision positions, external training, and participant in

productive chains), negative (first-level supplier and commercial banks

financing) and general (use of computers, higher education, and supplier of

governments) partial relationships.

Findings: The results show

that the partial relationships among diverse stakeholders are significant to

the innovation that is not registered nor acknowledged in Mexican SMEs, which

is an indicator of a dynamic sector that responds to the needs and expectation

of internal and internal factors in terms of the introduction of new products,

processes, marketing and organizational changes, showing a better approach to

understand the phenomena in small and medium business.

Keywords: Innovative

vocation, SMEs, Mexico, stakeholders, productive chain.

RESUME

Propósito: Las

pequeñas y medianas empresas (Pymes) son significativamente relevantes en la

economía mexicana, empleabilidad e innovación. En términos de comprender la

innovación informal, el presente trabajo analiza la “innovación clandestina”.

Diseño

metodológico: Utilizando los datos disponibles en la Encuesta Nacional sobre

Productividad y Competitividad de las Micro, Pequeñas y Medianas Empresas

(ENAPROCE), se analiza la correlación entre innovación organizacional, innovación

de marketing, de procesos y de producto para comprender su respectiva

interacción; después, se realizó una prueba de correlación parcial considerando

el número de certificaciones formales obtenidas (Marcas, Patentes, Modelo de

utilidad y Diseños industriales) como una variable de control para obtener los

coeficientes de correlación parcial. Las relaciones parciales entre grupos de

interés e innovación clandestina en las Pymes mexicanas se clasificaron en tres

categorías de correlaciones parciales: positiva (la persona que toma las

decisiones, las posiciones directivas y de supervisión, la capacitación externa

y la participación en cadenas productivas), negativas (proveedores de primer

nivel y financiamiento de bancos comerciales) y generales (uso de computadoras,

educación superior y ser proveedores de gobierno).

Resultados:

Los resultados muestran que las relaciones parciales entre diversas partes

interesadas son significativas para la innovación que se registra formalmente

en las Pymes mexicanas, lo cual representa un indicador relativo a un sector

dinámico que responde a las necesidades y expectativas de factores internos y

externos en términos de la introducción de nuevos productos, procesos, así como

cambios en marketing y de tipo organizacional, mostrando un mejor enfoque para

comprender el fenómeno en empresas pequeñas y medianas.

Keywords: Vocación innovadora, PYMES,

México, grupos de interés, cadena productiva.

![]()

INTRODUCCION

In terms of innovation, factors such as

changes in policies, markets, technology, industry structure, and institutions

have the potential to influence the introduction of new products, processes,

marketing, and organizational methods in any given company. Since innovation is

a relevant factor for companies and organizations to stay competitive, to be

productive, and even to survive in a turbulent context, is a substantially

important subject for research.

The concept

that was provided by Schumpeter in 1934 refers to innovation as the

implementation of goods that are new to consumers in terms of uniqueness or

higher quality, and also the implementation of new production methods, opening

of new markets, the use of new raw materials, considering new forms of

competition as well (Bazhal, 2016); also, it can be considered as a new or

improved product or process (or a combination thereof) that differs

significantly from the unit's previous products or processes and that has been

made available to potential users (product) or brought into use by the unit

(process) (Caplow, 1955).

Other relevant

authors define the concept in terms of new elements brought to the buyer,

whether or not new to the organization (Howard & Sheth, 1969), ideas that

can be replicated on a meaningful scale at practical costs (Senge, 1990), an

ability to discover new relationships, of seeing things from new perspectives

and to form new combinations from existing concepts (Evans, 1991).

The concept is

refereed even also to policies, structure, method, process, product or market

opportunity that the manager of a working business unit should perceive as new

(Nohria & Gulati, 1996), the creation of new association (combination)

product-market-technology-organization (Boer & During, 2001), that can be

related in a comprehensive concept from the manager view as the efficient

coordination of the elements in a social organism that enhances the evolution

process of any created invention of an individual regarding the introduction in

the market, the organization itself or the industry, resulting in a positive

impact in any way of profitability in a social organism.

As a useful

guide to understanding further the concept, the Oslo Manual suggests that

innovation is a new or improved product or process (or a combination thereof)

that differs significantly from the unit’s previous products or processes and

that has been made available to potential users (product) or brought into use

by the unit (process), according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development [OECD] and Eurostat (2018), which suggest the major importance

innovation has in any given company.

Since

innovation represents a complex concept to be understood in the reality of

organizations, the main goal of the analysis is to determine the effect of some

indicators related to innovation that can be considered as “underground

innovation” since is not reported nor acknowledged for any institution, but

exist in Mexican SMEs in forms of new products, processes, marketing or

organizational innovations and can be traced to the multiple and diverse interactions

of the company with their respective stakeholders; because of that, the

research question: How are stakeholders interactions correlated to

underground innovation in Mexican SMEs?

Literature review

Relevant aspects in measuring innovation

In terms of

understanding sources, mechanisms, and effects of innovation in organizations

it is necessary to measure both inputs (people and the training they receive,

physical and financial resources, and how they change over time) and outputs

(e.g., scientific papers that directly result from projects or programs)

(Perrolle & Moris, 2007).

Because

innovation has many components to be measured, it is possible to establish

categories related to those factors, in that sense we can understand as inputs,

factors related to people, money, processes; on the other hand, there are

outputs, such as cash returns; the third category can be defined as indirect

benefits, such as stronger brand and acquired knowledge, according to the

Boston Consulting Group [BCG] (2007); on the other hand, Fagerberg, Mowery,

& Nelson, (2005) argued that an important development has been the

emergence of new indicators of innovation inputs and outputs, including

economy-wide measures that have some degree of international comparability.

Also, some

concepts relate innovation with intensity and propensity, with a distinction

between the propensity to innovate at the level of undertaking or not

innovative activities, meanwhile, the decision on innovation intensity regards

how many resources are allocated to such activities, generally compared with

the overall firm's activity or that of its sector. (Eurostat, Devstat, &

Higher School of Economics of Moscu [HSEU], 2016).

The concept of

“underground innovation” in organizations

As the

definition suggests, "underground innovation" refers to the

introduction of new products, process, marketing, or organizational changes

that are not formally reported nor registered in any established institution or

governmental organization (in other words, represent an informal type of

innovation that do not count in the formal innovation national system); since

the context of many Mexican SMEs is oriented to a changing environment that

affects the possibility of survival for the organizations, it is necessary to

understand how the companies are innovating even if they are not necessarily

registering their innovations formally, but are essential for well-functioning

companies in an ever-changing environment.

Firstly, in

terms of informal innovation, the dataset of bibliometric information in the

website of Scopus shows that there is a positive tendency to research the

topic, with a peak of published articles located in recent years; also, the

countries that are the most prolific in the subject are United States, United

Kingdom, Netherlands, Australia, Germany, China, Canada, Italy, Spain and

France, and the related subjects are focused in social sciences, business,

management and accounting.

Following that

data, the most influential papers (due to the number of cites) refers to a work

of (Jansen,

Van Den Bosch and Volberda, 2006) which argue that, in addition to formal

controls, informal social relations determine the extent to which exploratory

and exploitative innovation can be developed, yet the impact of formal

hierarchical structure and informal social relations on exploratory and

exploitative innovation has not been studied in an integrated model. Focusing

on organizational units, this study contributes to previous research through

examining how formal and informal coordination mechanisms influence a unit’s

exploratory and exploitative innovation.

Another

relevant work is (Van Aken

and Weggeman, 2000), which

states that informal innovation networks are easier to create because of their

adaptability and fairly loose, cooperation agreements are better suited for the

uncertainties present at the environment, considering main factors such as

sharing risk, leverage of resources, injection of variety.

In the other

hand, (Conway,

1995) propose that many innovation studies have

also long highlighted the importance of informal boundary-spanning relationship,

in other word, represent means for sourcing ideas and information during the development

process based on multiple and continuous interaction; in that sense, the

presence of a certain informal network represents a relevant base for formal

innovation, given the nature of multiple

and free interactions among persons inside the organizations.

Those

interactions are the basis of social contacts and networks that represent the

underlying modes of transferring scientific and technical human capital into

work that compliments what is being called as individual endowments of tacit

and craft knowledge (Grimpe and

Hussinger, 2013), in a more comprehensive way of seeing

the complexity in the interactions inside organizational life, in where recent

models of innovation emphasize the relevance of interactions among firms,

customers, suppliers and institutions (Jensen et al., 2007), that allow firms to survive in a rapid

technological change by innovation based on interactions among agents (Conway,

1995) which also can be considered as relevant

interest parties whom have a certain stake in the company.

In that sense,

behaviors that make organizations responsive to the environment can encourage

diverse types of innovation, since it is based on a process that is stimulated

by the interaction of individuals and groups with different backgrounds,

benefits, and perspectives, in where the ability to interact constructively and

work in new ways is crucial for the innovation performance (Devaux et al., 2009);

those individuals and groups are the stakeholders of the company, indeed.

Following that

though, coordinated action between companies and their stakeholders is the

central character of the generation of innovative products, processes,

services, technologies, and business models that are capable of being viable

economically, environment-friendly, and socially responsible (Geissdoerfer,

Savaget, Paulo, Evans, & Steve, 2017), since creativity can occur when

individuals interact when is possible to get new ideas, insights and even

knowledge (OECD, 2017).

Influence of

stakeholder’s interaction on innovation

The influence

of relevant stakeholder in the life of organizations, previous research such as

Dollinger (1990) analyzed fragmented industries and outlines that the actors of

small firms search for forms of interdependence to survive (Granata, Garaudel,

Gundolf, Gast, & Marques, 2016) and adapt to environments of uncertainty in

the industry.

A wide

accepted concept definition for these interest parties as relevant groups such

as shareholders, customers, suppliers, and any other actor "who can affect

or is affected by the organization's purpose" (Freeman, 1984, p.52) who

are defined in terms of tree relationship attributes power (have certain access

to coercive, utilitarian or normative means to impose its will), legitimacy

(the legitimate right to claim a determine response in a relationship) and

urgency (the time-sensitive call for immediate attention) (Mitchell, Agle,

& Wood, 1997).

Consequently,

different stakeholders can affect companies representing elements that drive

innovation can be related to the value generated among organizations when

trying to provide different types of benefits-oriented to satisfy the needs and

expectations of various stakeholders (OECD & Eurostat, 2018).

For this

reason, companies must collaborate with various interest parties related to

input and output factors taking into account some representative groups of

interest such as customers, suppliers, and other partners, competitors, and

different institutions (Majava, 2016), that are relevant sources of

information, knowledge, and even a relevant change in the industry.

Besides, in a

multiple-level perspective, there is a recognition that governments, firms, and

other interest parties have a determinant role in the changes introduced to the

organizational system, where even policymakers are relevant in terms of

managing dynamics of diverse nature of transactions (Greenacre, Gross, &

Speirs, 2012), which are related to the industry.

Following that

thought, for companies such as SME´s, elements like knowledge spillovers,

access to networks, and engaging in collaboration with other players represent

an essential influence for innovation, in where globalization has brought new

opportunities for cross-border collaboration and interchange of ideas, finance,

skills, technologies from abroad, with a considerable impact in productions of

goods, services, patents, licenses, among others (OECD, 2017).

Hence, what

could be called the “entrepreneurial ecosystem”, refers mainly to “the

interaction that takes places between organizations and individual stakeholders

that are relevant for the companies” (Isenberg 2010 cited by Sorama &

Joensuu-Salo, 2016, p.2), being an essential aspect of management issues, even

in terms of commercialization activities, that must conduct networked market

actors, where new products must attract stakeholders for the diffusion of

innovation in the market (Engez, 2018, p. 64). In other words, “nuanced

knowledge of stakeholders is closely connected to the potential for product and

process innovations and the creation of new inter-organizational relationships”

(Barringer and Harrison 2000 cited by Freeman et al., 2010, p.34).

After a substantially search in bibliography, it is relevant to highlight

that the basis of such interactions related to innovation can be traced to

genre diversity in leadership positions (Romero-Martínez, Ana M.;

Montoro-Sánchez, Ángeles; Garavito-Hernández, 2017; Robinson y Dechant; 2011), level of

training and education (Morales et al., 2016; Popescu y Crenicean;

2012), participation

in supply chains (national and international) (Alania, 2017; Bustillos and Carballo, 2018) and aspects

related to management and organizational subjects (Oliveira et al., 2017; Adams, Bessant and Phelps, 2017), as it is included

in table 1.

MATERIAL AND METHODS.

The data for the analysis was extracted from the website of the National

Survey of Productivity and Competitiveness of Micro, Small and Medium

Enterprises (ENAPROCE in Spanish), which is an instrument of national reach

regarding managerial and entrepreneurial skills of the enterprises, that allows

knowing characteristics of operation and

development of such companies.

This survey was elaborated by a collaboration of organisms such as the National

Institute of Statistics and Geography

(INEGI in Spanish), the national institute of entrepreneurship (INADEM in

Spanish), and the National Bank of Foreign Commerce (Bancomext in Spanish) in

2018.

The size of the sample was 22,188

companies, distributed in Manufacturing (5,189), Commerce (7,130), and Services

(9,689); in terms of size, 18,886 were Small and Medium enterprises and 3,302

were Microenterprises. The information was collected from October 1st

to November 30th, in the year 2018. The dataset is organized

considering the following conceptual definition of each included variable, as

follows.

|

Table 1 Conceptual

definition of the considered variables |

||||

|

Name |

Class |

Definition |

References |

|

|

Prod_Inv |

Product innovation |

Innovation indicator |

New products (goods and services) or the substantial improvement of

existing ones introduced to the market |

(OECD & Eurostat, 2018; INEGI, 2019). |

|

Proc_Inv |

Process innovation |

Innovation indicator |

The inclusion in the production process of new processes (includes

methods) or the substantial improvement of existing ones. |

|

|

Org_Inv |

Organizational innovation |

Innovation indicator |

The introduction of a new organizational method in the practices, the

organization of the workplace, or the external relations of the company. |

|

|

Mkt_Inv |

Marketing innovation |

Innovation indicator |

The application of a new marketing method that involves significant

changes in the design or packaging of a product, positioning, promotion, or

pricing |

|

|

Industrial_

property |

Industrial property |

Formal innovation |

Brands, Patents, Utility Models, and Industrial designs registered

formally as industrial property titles, acknowledged by an institutional or

governmental organization. |

|

|

MPTD |

A male person taking decisions |

Stakeholder related |

Number of men in positions able to take decisions |

(INEGI,

2019; Monroy

Merchán, 2019; Manosalvas

Vaca et al., 2020; Romero-Martínez, Ana M.;

Montoro-Sánchez, Ángeles; Garavito- Hernández, 2017) |

|

FPTD |

A female person making decisions |

Stakeholder related |

Number of women in positions able to take decisions |

|

|

FDSP |

Female in Directive and Supervision position |

Stakeholder related |

Number of females that are in Directive and Supervision positions |

|

|

MDSP |

Male in Directive and Supervision position |

Stakeholder related |

Number of males that are in Directive and Supervision positions |

|

|

HEdu |

Higher education |

Stakeholder related |

Level of education considering Bachelor, Specialty and Postgraduate. |

(Romero-Martínez,

Ana M.; Montoro-Sánchez, Ángeles; Garavito- Hernández, 2017) |

|

ETraining |

External training |

Stakeholder related |

Considers hiring external trainers or agreements are made with

universities or educational and technical training centers. |

|

|

EIncome |

Earned income |

Stakeholder related |

The total amount that the company obtained for all those activities of

production, marketing, or provision of services performed during the

reference year. |

(López-Mielgo,

Montes-Peón & Vázquez-Ordás, 2012; Zegarra, 2006; Bárcenas

et al., 2009) |

|

PPCh |

Participation in productive chains |

Stakeholder related |

The total number of companies that participated during the period 2016

and 2017 through contracts or programs of collaboration in production chains

(integrated processes with other economic units for the design, supply,

production, distribution, or marketing of goods, parts, or components or

services). |

(Martínez

and Pérez, 2006; Fernández,

2003; Alania,

2017; Bustillos and Carballo, 2018; Olea-Miranda, Contreras and

Barcelo-Valenzuela, 2016; Luzzini et al., 2015; Rosell and Lakemond, 2012; He, Gan

and Xiao, 2021) |

|

SGovn |

Supplier of government |

Stakeholder related |

The total amount of companies that are suppliers of governments |

|

|

Exports |

Exports |

Stakeholder related |

The total amount of exports that the company made during 2017 in

Mexican pesos |

|

|

SEComp |

Supplier of exporting companies |

Stakeholder related |

The total amount of companies that are suppliers of exporting

companies |

|

|

FSPCh |

First level supplier (productive chains) |

Stakeholder related |

First-level supplier of raw materials, parts, or services (they are

incorporated directly into final goods). |

|

|

SLPCh |

Second level supplier (productive chains) |

Stakeholder related |

Supplier of raw materials, parts, or second-level services (they are

incorporated into other intermediate goods). |

|

|

MPCh |

Marketer (productive chains) |

Stakeholder related |

Companies that carry out their act of commerce, that is, they acquire

goods or merchandise for its subsequent sale, in which two intermediaries

interfere, the producer and the consumer. |

|

|

SCImp |

Solution and continuous improvement |

Stakeholder related |

Any organizational problem found was solved and actions were taken to

ensure that it did not happen again. and a process of continuous improvement

was started to anticipate similar problems. (Problems with inventories,

transportation problems, technical failures, handling of staff, customer

service, etc.) |

(Lendel, Hittmár and Siantová, 2015; Stouten, Rousseau and De Cremer, 2018; Kalay, 2015; Adams, Bessant and Phelps, 2017) |

|

UComp |

Use of computers |

Stakeholder related |

Companies that use electronic equipment that serves to process

information following instructions stored in the software. |

|

|

CBF |

Commercial banks financing |

Stakeholder related |

Loans or financing of any type granted by commercial banks. |

(Abel-Koch, Gerstenberger and Lo, 2015; Rubiano et al., 2007) |

|

Source: Own elaboration based on ENAPROCE (2018). |

||||

All the information will be treated by the calculation of the partial

correlation coefficient considering industrial property as the control

variable, that will measure the correlation among variables controlling for the

relationship apport of the formal innovation correlation coefficient, leaving

only the correlation among variables while controlling the effect of formal

innovation measured by the variable Industrial_property (Brands,

Patents, Utility Models, and Industrial designs registered formally as

industrial property titles, acknowledged by an institutional or governmental

organization).

In that sense, to test

the hypothesis, the variables involved with underground innovation are

calculated with a partial correlation coefficient, controlling the effect of

“industrial property” setting it as control variable; in this sense, the

results will show the correlation among all the considered variables in terms

of informal innovation (namely, all the innovation that occur considering

formal innovation such as Brands, Patents, Utility Models, and Industrial designs registered

formally as industrial property titles, acknowledged by an institutional or

governmental organization), taking into account the

calculation for partial correlation coefficient for all the remained variables,

as follows (Amaral, 2017, p.5).

Formula: Partial correlation

|

|

|

Source: Amaral

(2017, p.5) |

The latter formula allows to determine a measure of “standardized”

partial association among the outcomes (Product, Process, Marketing, and

Organizational innovation) y and each of the covariates in x'= (X1, . XK)

related to the indicators regarding stakeholders of the companies that

participated in the survey.

RESULTS

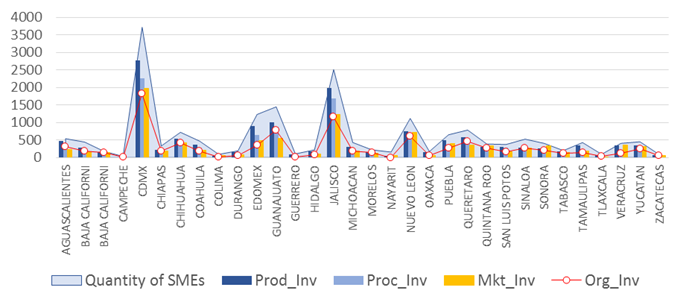

The data related to each type of innovation (Organizational, Marketing,

Process, and Product) has similar behavior in all the SMEs of the different

Mexican state, as it shows in the next figure.

As is possible to see in the former figure, the different kinds of

innovation appear to have similar behavior in the SMEs grouped by state, where

Mexico City (CDMX) is acknowledged as the “Frontier state” since presents the

higher record of innovation in the country, followed by Jalisco, Guanajuato,

and State of Mexico (Edomex).

|

Figure 1: Total sum of

Product Innovation, Process Innovation, Marketing Innovation, and

Organizational innovation in Mexican SMEs grouped by state |

|

|

|

Source: Own

elaboration (2021). |

Correlation

and Partial correlation indexes

Now, to determine the adequate correlation coefficient technique to use, an

important step is to test if the quantitative data is normally distributed; in

that matter, we performed a normality test to the set of information available,

obtaining the following results.

|

Table 3 Normality test with

a sample of fewer than 50 subjects using Shapiro-Wilk test |

|||

|

|

Shapiro-Wilk |

||

|

Statistic |

df |

Sig. |

|

|

Prod_Inv |

.630 |

32 |

.000 |

|

Proc_Inv |

.607 |

32 |

.000 |

|

Org_Inv |

.654 |

32 |

.000 |

|

Mkt_Inv |

.653 |

32 |

.000 |

|

MPTD |

.671 |

32 |

.000 |

|

FPTD |

.708 |

32 |

.000 |

|

FDSP |

.685 |

32 |

.000 |

|

MDSP |

.676 |

32 |

.000 |

|

HEdu |

.523 |

32 |

.000 |

|

ETraining |

.671 |

32 |

.000 |

|

EIncome |

.659 |

32 |

.000 |

|

SGovn |

.642 |

32 |

.000 |

|

Exports |

.790 |

32 |

.000 |

|

SEComp |

.294 |

32 |

.000 |

|

SCImp |

.660 |

32 |

.000 |

|

CBF |

.720 |

32 |

.000 |

|

PPCh |

.697 |

32 |

.000 |

|

FSPCh |

.638 |

32 |

.000 |

|

SLPCh |

.657 |

32 |

.000 |

|

MPCh |

.671 |

32 |

.000 |

|

UComp |

.573 |

32 |

.000 |

|

Source: Own elaboration using SPSS (2021). |

|||

As we can see in the former table, the quantitative data is normally

distributed, so is possible to perform a Pearson correlation test to understand

the direction and strength of the relationship among types of innovation. To

make the hypothesis contrast, we proceed to calculate Pearson correlation

coefficient for each type of innovation, obtaining the following results.

|

Table 4 Parametric Correlation test for variables directly

related to innovation in Mexican SMEs |

|||||

|

Correlations |

|||||

|

|

Prod_Inv |

Proc_Inv |

Org_Inv |

Mkt_Inv |

|

|

Prod_Inv |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

.995** |

.981** |

.978** |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

N |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

|

|

Proc_Inv |

Pearson Correlation |

.995** |

1 |

.987** |

.974** |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

|

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

N |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

|

|

Org_Inv |

Pearson Correlation |

.981** |

.987** |

1 |

.979** |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

.000 |

|

.000 |

|

|

N |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

|

|

Mkt_Inv |

Pearson Correlation |

.978** |

.974** |

.979** |

1 |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

N |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

|

|

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level |

|||||

The former table shows that there is a strong and significant

relationship among the variables directly related to innovation (>0.9). Continuing

with the analysis, when we applied a partial correlation test using the

industrial property is an important condition to control the effect of formal

innovation in the results of each company, leaving results of correlations

considering relationships of innovation outside the formality; in other words,

underground innovation measured by a partial correlation considering formal

innovation measured as registered industrial property staying constant,

obtaining the following results.

|

Table 5 Partial Correlation

using “Industrial_property” (formal innovation) as a control variable for

Product Innovation, Process Innovation, Organizational Innovation, and

Marketing Innovation |

|||||

|

|

|

Prod_Inv |

Proc_Inv |

Org_Inv |

Mkt_Inv |

|

Prod_Inv |

Rho |

1.000 |

.873 |

.687 |

.643 |

|

Sig. |

. |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

df |

0 |

29 |

29 |

29 |

|

|

Proc_Inv |

Rho |

.873 |

1.000 |

.803 |

.567 |

|

Sig. |

.000 |

. |

.000 |

.001 |

|

|

df |

29 |

0 |

29 |

29 |

|

|

Org_Inv |

Rho |

.687 |

.803 |

1.000 |

.709 |

|

Sig. |

.000 |

.000 |

. |

.000 |

|

|

df |

29 |

29 |

0 |

29 |

|

|

Mkt_Inv |

Rho |

.643 |

.567 |

.709 |

1.000 |

|

Sig. |

.000 |

.001 |

.000 |

. |

|

|

df |

29 |

29 |

29 |

0 |

|

|

Source: Own elaboration using SPSS (2021). |

|||||

The partial correlation coefficient modifies the former results in terms

of relations among variables, resulting in high correlation (Prod_Inv &

Proc_Inv; Proc_Inv & Org_Inv;

Org_Inv & Mkt_Inv)

and moderated correlation (Prod_Inv & Org_Inv; Prod_Inv & Mkt_Inv;

Proc_Inv & Mkt_Inv); this noticeable change shows that the control variable

“Industrial_property” has a relevant effect in terms of correlations among

variables directly related to innovation in Mexican SMEs.

Continuing with the analysis, leaving the control variable

“Industrial_property”, the results obtained of the partial correlation among

all the considered variables show the following results. The information

contains the interpretation of each result in terms of significance (p>0.05)

and strength of relationship among variables (Negligible < 0.19; 0.2 < Weak < 0.39; 0.4 < Moderated < 0.69; 0.7

< High < 0.89; 0.9 < Very High < 1).

|

Table 6 Partial

correlations among innovation with "Industrial property" as the

control variable |

||||

|

Variable |

Prod_Inv |

Proc_Inv |

Org_Inv |

Mkt_Inv |

|

MPTD |

Weak |

Negligible |

Weak |

Moderated |

|

FDSP |

Weak |

Negligible |

Weak |

Moderated |

|

ETraining |

Weak |

Negligible |

Weak |

Moderated |

|

SEComp |

Weak |

Negligible |

Weak |

Negative negligible |

|

SCImp |

Weak |

Weak |

Weak |

Moderated |

|

MPCh |

Weak |

Weak |

Moderated |

Moderated |

|

FPTD |

Moderated |

Weak |

Weak |

Moderated |

|

HEdu |

Moderated |

Moderated |

Moderated |

High |

|

SGovn |

Moderated |

Moderated |

Moderated |

Moderated |

|

UComp |

Moderated |

Weak |

Moderated |

Moderated |

|

CBF |

Negative weak |

Negative moderated |

Negative weak |

Negative negligible |

|

FSPCh |

Negative weak |

Negative moderated |

Negative negligible |

Negligible |

|

PPCh |

Negative negligible |

Negative weak |

Weak |

Weak |

|

MDSP |

Negligible |

Negative negligible |

Negligible |

Weak |

|

EIncome |

Negligible |

Negative negligible |

Negative negligible |

Weak |

|

Exports |

Negligible |

Negative negligible |

Negligible |

Negligible |

|

SLPCh |

Negligible |

Negative negligible |

Negative negligible |

Negligible |

|

Mkt_Inv |

Moderated |

Moderated |

High |

|

|

Org_Inv |

Moderated |

High |

||

|

Source: Own elaboration using SPSS (2021). |

||||

The former table highlights the results of significative moderated and

high correlations among the considered variables, taking into account that

Industrial property (formal innovation) is considered as the control variable,

where is possible to categorize the results in terms of positive, negative, and

general relationships.

|

Table 7 Categories

of partial correlations controlling the variable “Industrial property”

(formal innovation) |

||

|

Variable |

Correlation |

|

|

Male person taking decisions Female in Directive and Supervision position External training Female person making decisions Marketer participant in productive chains |

Marketing innovation, Product innovation and Organizational innovation |

|

|

Negative and significative partial relationships |

First-level supplier of raw materials,

parts, or services Commercial banks financing |

Process innovation |

|

Positive and significative general partial relationships |

Use of computers Higher education Supplier of government |

Product, Process, Marketing, and Organizational

Innovation |

|

Source: Own elaboration

(2021). |

||

The three categories mentioned before are relevant to better understand

the relationship among different stakeholders considering industrial property

as the control variable since the innovation that born out of the dynamic

relationship with the context of an important number of Mexican SMEs can be

related to variables outside of what is considered to be formal innovations.

DISCUSSION

The present study analyzed the relations among

variables related to different stakeholders on the innovation of Mexican SEMs

using a partial correlation coefficient test for all the independent variables

and indicators related to products, process, marketing, and organizational

innovations as the quantitative components of innovation in those companies.

First, the control variable regards industrial

property, is considered as a quantitative indicator strongly related to formal

innovation, since is the number of innovations that are acknowledged for governmental

or institutional organizations, and based on that, the partial correlations

show a type of innovation related to stakeholders that are not registered nor

institutionally acknowledged by any institution; an economic indicator that is

being considered as "underground innovation".

Whit that goal, the results were organized in

three main categories: variables with positive and significative partial

relationships, variables with negative and significative partial relationships,

and variables with positive and significative general partial relationships.

The first category presented the variable

“Male person taking decisions”, which is related to the number of men in

positions able to take decisions, shows a moderated partial correlation with

marketing innovation, which is the total sum of the application of a new

marketing method that involves significant changes in the design or packaging

of a product, positioning, promotion or pricing; other variables with a similar

result regarding Marketing innovation are “Female in Directive and Supervision

position” and “External training”, which is a quantitative measure for

companies hiring external trainers, making training agreements with

universities, educational and technical training centers.

In what it comes to the variable "Female

person taking decisions", the results suggest a moderated partial

correlation with product innovation, in terms of the introduction of new

products or the substantial improvement of existing ones.

On the other hand, the variable "Marketer

participant in productive chains” has a moderated partial correlation with

organizational innovation, in terms of the introduction of a new organizational

method in the practices, the organization of the workplace, or the external relations

of the company.

In what it comes to the second category related

to negative and significative partial relationships, the results showed that

the variable “First level supplier of raw materials, parts,

or services”, which are incorporated directly into final goods, as well as the

variable related to “Commercial banks financing” showed

a negative moderated partial correlation with process innovation, that is

represented by the inclusion in the production process of new processes

(includes methods) or the substantial improvement of existing ones.

Finally, the third category related to

positive and significative general partial relationships, then the variable

“Use of computers”, that considers an indicator about the use of electronic equipment that serves to process information following

instructions stored in the software; the variable “Higher

education" that refers to a level

of education (Bachelor, Specialty and Pos-graduate) and the

variable “Supplier of government”, which accounts for

the number of companies that reported participating in that productive chain, presented a moderated positive partial correlation with all the

indicators related to innovation (Product, Process, Marketing and

Organizational) indicators.

CONCLUSIONS

The

outcomes presented leave open lines of research and future developments in the

subject of gender diversity, education and regional innovation matters, including

the need of further development of new works related to underground innovation in

SMEs, to better understand this nature of innovation in different social,

political, and economic contexts.

Specifically

in terms of management capabilities affecting innovation performance, is

relevant to consider the high level of responsibility for strategic and

critical decision making as a critical element in maintaining a dynamic process

of decision making and continuous improvement that permit the necessary

connections that encourage product and process innovation (Ruiz-Jiménez and

Fuentes-Fuentes, 2015).

In that

sense, the diversity of way of thinking and decisions processes in management

are significant incentives that can function as a gateway to innovation, where

cultural diversity represent an adequate environment to promote the needed

freedom to the formation of innovative ideas by the contributions of flexible

and open-minded individuals (Özmutaf et al., 2015)

Finally, In what it comes to gender diversity in organizations, in Mexico

women are less likely to have access to entrepreneurship training, a situation

that can be explained by factors including low levels of awareness of available

support, unappealing training programs, selection bias in program in-take, or

even issues of accessibility to such resources (OECD, 2019); this is

clearly a situation that can be improved by designing adequate public policies

to promote gender diversity in organizations, promoting innovation

consequently.

REFERENCES

Amaral, E. (2017) “Lecture

24 : Partial correlation, multiple regression, and correlation”, pp.

405–441. Retrieved from:

http://www.ernestoamaral.com/docs/soci420-17fall/Lecture24.pdf

Bazhal, I. (2016). The

Theory of Economic Development of J.A. Schumpeter: Key Features.

Development Aid and Sustainable Economic Growth in Africa, (69883), 43–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-38936-3_2

BCG. (2007). Measuring

Innovation 2007. A BCG Senior Management Survey. Available at:

https://web-assets.bcg.com/b0/b2/196ef6254aa5ba31c7485388d312/2007-innovation-report.pdf

Caplow, T. (1955). The

Definition and Measurement of Ambiences. Social Forces, 34(1), 28–33.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2574256

Devaux, A., Horton, D.,

Velasco, C., Thiele, G., López, G., Bernet, T., … Ordinola, M. (2009).

Collective action for market chain innovation in the Andes. Food Policy, 34(1),

31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.10.007

Engez, A. (2018).

Stakeholders contributing to the commercialization of a radical innovation at

global markets: A single case study. Retrieved from: https://dspace.cc.tut.fi/dpub/bitstream/handle/123456789/26571/Engez.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Eurostat, Devstat, &

Higher School of Economics of Moscu. (2016). New methods for the quantitative

measurement of innovation intensity. Retrieved from https://www.dialogic.nl/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/DevStat_WP1-New-methods-for-the-quantitative-measurement-of-innovation-intensity.pdf

Fagerberg, J., Mowery,

D., & Nelson, R. (2005). The Oxford Handbook of Innovation. The Oxford

handbook of cognitive and behavioral therapies.

https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199988693.001.0001

Freeman, E., Harrison,

J., Hicks, A., Parmar, B., & Colle, S. de. (2010). Stakeholder Theory: The

state of the art. Retrieved from: https://silo.pub/stakeholder-theory-the-state-of-the-art.html

Geissdoerfer, M.,

Savaget, P., Paulo, Evans, S., & Steve. (2017). The Cambridge Business

Model Innovation Process. Procedia Manufacturing, 8, 262–269.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2017.02.033

Granata, J., Garaudel,

M., Gundolf, K., Gast, J., & Marques, P. (2016). Organisational innovation

and coopetition between SMEs: a tertius strategies approach. International

Journal of Technology Management, 71(1/2), 81.

https://doi.org/10.1504/ijtm.2016.077975

Greenacre, P., Gross, R.,

& Speirs, J. (2012). Innovation Theory: A review of the literature.

Imperial College Centre for Energy Policy and Technology (ICEPT), (May), 1–49.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2008.04.067

Kwak, C., &

Clayton-Matthews, A. (2002). Multinomial logistic regression. Nursing Research,

51(6), 404–410. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200211000-00009

Majava, J. (2016).

Ecosystem stakeholder analysis : an innovation-driven enterprise ’ s

perspective. Managing Innovation and Diversity in Knowledge Society Through

Turbulent Time. Management, Knowledge amd Learning. Joint International

Conference 2016 (pp. 373–379). Retrieved from: http://www.toknowpress.net/ISBN/978-961-6914-16-1/papers/ML16-078.pdf

Mitchell, R., Agle, B.,

& Wood, D. (1997). Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience:

Definint the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. Academy of Management

Review, 22(4), 853–886. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1997.9711022105

OECD. (2017). Enhancing

the Contributions of SMEs in a Global and Digitalised Economy. Meeting of the OECD

Council at Ministerial Level, (June), 1–24. Retrieved from:

https://www.oecd.org/mcm/documents/C-MIN-2017-8-EN.pdf

OECD, & Eurostat.

(2018). Oslo Manual. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264304604-en

Perrolle, P., &

Moris, F. (2007). Advancing Measures of Innovation: Knowledge Flows, Business

Metrics, and Measurement Strategies. Retrieved from:

http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/workshop/innovation06/.

Sorama, K., &

Joensuu-Salo, S. (2016). A Case Study of Entrepreneurial Ecosystem related to

Growth Firms. Retrieved from: https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/122436